|

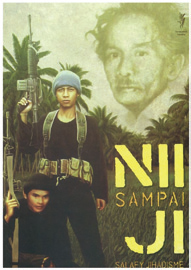

NII Sampai JI, Salafy Jihadisme Di Indonesia (NII to JI, Salafy Jihadism in Indonesia) |

“Akhi (Brother), let your life be filled with the murder of infidels. Did not Allah order us to kill them all as they have killed us and our brothers and sisters? Aspire to be the butcher of infidels. Teach your children and grandchildren to be murderers and terrorists against the entirety of the infidels. Really, akhi, that title (terrorist) is better for us than to be a Muslim who does not care how the blood of his brothers is spilt as they are slaughtered by infidels …” This disturbing note is an excerpt from a letter written by Imam Samudra, the mastermind of the 2002 Bali bombings who was executed in 2008. He wrote the invocation during his imprisonment by “the Indonesian infidel ruler.” The first Bali bombings, in which 202 people died and another 300 were injured, opened the eyes of many to the existence of an ideology, later identified as Salafy Jihadism (Ed: Normally transcribed from Arabic as Salafi), which had in fact been entrenched in Indonesia for generations. The emergence of the seemingly new ideology raised a lot of questions. Where did it come from? Why and how could the ideology grow in this country? What are the roots of the jihad movement in Indonesia? How and why could Islamic groups in Indonesia adopt and implement a view often identified with al Qaeda?

Seasoned Indonesian journalist and researcher Solahudin is quite successful in answering these questions. His book is an analytical and comprehensive, as well as impartial, account of the history of jihad in Indonesia, from the early period of rebellion by Darul Islam back in the 1940s to the Bali bombings in 2002. Indeed, Solahudin goes as far back as the 13th century to find the roots of Salafy Jihadism. Established by a Syrian ulema named Syaikh Ibn Taymiyyah, Salafy refers to an Islamic movement that strives to purify the understanding of Islam according to the beliefs of the Salafy. They lived at the time of the Prophet Muhammad, his disciples and those disciples’ own students. They are believed to have enjoyed unrivaled competence in the understanding of Islam because they learned from the original sources.

The movement underwent development and modification from time to time, including a shift of some adherents to Wahhabism, a radical Islamic school of thought that is now the dominant religious school in Saudi Arabia. Despite the modifications, the two groups share a similar purpose, which is to emulate the Salafy, including the way in which the Prophet and his disciples dressed, to the enforcement of Islamic Shariah and jihad against infidels. This latter concept, much debated within Muslim societies, is usually translated in terms of violence and war, even to allowing the murder of women and children.

In Indonesia in the 1940s, Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosoewirjo and his Darul Islam movement developed an ideology similar to Salafy Jihadism. Solahudin’s book chronicles in detail and with rich narration and nuances the journey of Darul Islam through the years, its influence on current jihad movements and the modification of Darul Islam’s doctrine by followers who combined it with Salafy Jihadism from the Middle East. Solahudin also traces the international relationships of jihadis in Indonesia from the late 1970s, from efforts to raise funds from Libya, to inspiration from the Iranian revolution, the involvement in and military training in Afghanistan, and the connections with both the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) in the Philippines and with al Qaeda.

It is interesting to note that the history of jihadi groups in Indonesia has been highlighted by internal debates and conflicts over ideological differences, which shows that their doctrine is not monolithic. Like many radical groups, the principles and ideologies of jihad are often inconsistent and their arguments full of holes. The Salafy Jihadis in Indonesia easily label others, including fellow Muslims, as infidels. At other times, the groups borrow from other schools of thought, such as Shiite and Sufism, which they initially denounced as infidel teachings, and then incorporate them into their own principles as they see fit. The jihadi groups have also shown a lack of organizational ability and effective leadership, with the community ripe with internal conflicts and disputes that in some cases have ended with the assassination of group members or leaders and the establishment of new groups.

The Salafy Jihadis are by no means as invincible as they project themselves to be. Solahudin provides a nearly comical account of how Darul Islam planned several attempts to kill former President Soeharto, going as far as purchasing explosives in Malaysia but never carrying out its plans. When Soeharto stepped down in 1998, Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), an offshoot of Darul Islam, was in a state of confusion as to which enemy to fight, while the arrival of the democracy that it had despised for so long turned out to be beneficial to its existence. Radical groups find fertile ground in war and conflict. In Indonesia, as shown by this book, radical Islamic groups also thrive because they are utilized by the authorities. The book shows how political, military and intelligence figures during the New Order regime manipulated the mujahids for political interests. One reform-era political party invited JI members to become party members.

Growing up close to Darul Islam’s bases in West Java province, Solahudin is familiar with the culture and discourse about it and other Islamist groups. He draws from extensive sources, not only from the different radical groups themselves, but also from intelligence reports of the Indonesian military and police, court reports and interviews with jihadis both active and inactive. The author’s ability to maintain a distance from his sources and yet never be judgmental is admirable.

The book unfortunately suffers from poor editing, with typographical and grammatical errors to be found literally on every other page, with much repetition of sentences. Poor quality cover art also makes the book looks much less important than it really is. To do the book justice, the publisher should fix the editing problems and translate the book into English to reach a wider audience, given the importance of its account of jihad ideologies and movements in Indonesia.

%20resized.png)