Summary

The refugee crisis in Europe is doing more than just driving wedges between EU member states — it is also changing national demographics across the Continent. Populations in all European countries are already aging and many will soon begin to shrink, bringing fiscal hardships to economies. Though immigration can help foster economic growth, it can also open the door for political and social conflict. And as Europe deals with its third major wave of migration in 15 years, those very challenges are prompting European nations to consider reforming their immigration policies.

Analysis

As fertility rates drop and life expectancy grows, demographic change poses a major threat to the post-war economic model that predominates in Europe, which assumes a large workforce that can pay enough taxes to support the young and the old. Many governments reacted to the falling birth rate by offering increasingly generous benefits for families having children. But these policies have made a limited impact. Even in Sweden, where generous parental benefits did lead to modest improvements in fertility rates, childbirths have been below the replacement level for more than two decades.

Immigration, however, can mitigate the process of demographic change. The logic is simple: If a country cannot produce enough workers domestically, it can always import them. In principle, new workers fill labor shortages and raise domestic demand, causing firms to expand and hire new workers. Highly skilled immigrants contribute to specializing the economy, while low-skilled immigrants often take jobs that the locals will not. In addition, more workers means a larger tax base, which improves the fiscal situation of receiving countries and helps governments cover the cost of supporting older locals. However, the reality is more complicated.

Demographic change

The current refugee crisis in Europe has often been presented as a fight between generous countries (such as Germany, which agreed to take a large number of asylum seekers) and selfish nations (most notably the United Kingdom, which only reluctantly decided to accept more people). But the actual demographic situation in each nation helps elucidate their behavior.

According to EU projections, Germany will lose some 10 million people between 2020 and 2060 because of demographic change. The country's population will also become much older: during the same period the old-age dependency ratio (the percentage of people aged 65 and over compared with people between 15 and 64) will go from 36 percent to 59 percent, one of the highest in Europe. As a result, Germany's workforce is projected to decline 25 percent by 2060. This will create fiscal challenges for Berlin, including higher spending on pensions and healthcare.

Demographic change will be milder in the United Kingdom, which by mid-century will be the most populated country in Europe (Britain's population has been projected to reach 80 million by 2060, from 67 million in 2020). On average, the British population will be older than it is today, but the old-age dependency ratio will only be at 43 percent in 2060 from 30 percent in 2020, one of the lowest in Europe. Unlike Germany, the British workforce will increase by 10 percent between 2020 and 2060. At 1.9 children per woman, the United Kingdom has one of the highest fertility rates in the European Union.

These statistics partially explain the differing reactions in Berlin and London to the refugee crisis. Germany is far more in need of imported labor than the United Kingdom. Most asylum seekers arriving in Germany are men and women of working age with their children, who will hopefully join the labor force in the next decade. And while the newcomers will not entirely reverse the ageing and shrinking of Germany's population, they will assuage it somewhat.

However, these examples still do not offer the full picture of the situation. The problem with immigration is that what makes sense from an economic point of view is not necessarily acceptable from a political point of view. In Europe, demographic needs are not the only, or even the most important, drivers of government policy.

The politics of demographics

Over the past 15 years, Europe has experienced three notable migration periods. The first took place between 2004 and 2007, when the European Union expanded to the east and workers from densely populated countries such as Poland and Romania could move to Western Europe more easily. The second big wave began in 2009, when the crisis in the European periphery forced workers to move to the Continent's economic core in search of jobs. The third and current wave involves hundreds of thousands of people from the Middle East and other unstable areas trying to request asylum in Europe.

Each immigration wave has stirred political conflict. When countries from the former Communist bloc joined the European Union in the mid-2000s, several governments temporarily restricted workers from the new member states from entering. In those countries without immigration restrictions, political backlash followed. This occurred in the United Kingdom, where an immigration spike, most notably from Poland, helped give rise to the anti-immigration UKIP party.

While the second, periphery-to-core migration wave was not particularly disruptive for the receiving countries, it has hurt the European periphery. In countries such as Portugal, Spain or Greece, emigration offers some relief to the unemployment crisis, as there are fewer people competing for jobs. But it also creates the serious threat of a brain drain as people get their education for free in universities in the European periphery and then go to work for companies in core countries such as France and Germany. Even as countries in the European periphery see some modest growth, most of them will still have trouble drawing talent back from the core.

The current migration crisis is substantially different, as most of the new migrants are looking for asylum in Europe. They do not hold European passports, initially making it harder for them to find a job. Many are Muslim, which makes them a target for far-right and nationalist groups that see them as a threat to European culture. Recent attacks on migrant shelters in eastern Germany and the electoral growth of anti-immigration parties, such as the Sweden Democrats, exemplify the kind of animosity many immigrants face in Europe. These migrants are also throwing into question the entire EU immigration system, as member states are struggling to come up with a comprehensive solution to the crisis.

Domestic political conditions also affect the behavior of countries, especially ones that could use extra workers. Poland will hold elections in October; with the incumbent conservative government already losing votes to the nationalist opposition, Warsaw is reluctant to accept a mandatory quota of immigrants during the electoral campaign. Moreover, recent statements by Polish officials suggest their country would only accept Christian asylum seekers.

Hungary's government is under similar pressure from the nationalist right to adopt an anti-immigration stance. And the Baltic states, where immigration-friendly policies would make sense given abysmal fertility and high emigration, believe they are simply too small to deal with a spike in asylum requests.

Tough reforms ahead

The migration crisis will require legal and political reforms in Europe. Many asylum seekers and refugees face long waits before they are allowed to work. Germany is one of the few European states trying to solve this issue. Only two years ago, a refugee was not allowed to work during the first 12 months in Germany. Recent reforms have reduced the waiting time to three months.

But this only applies to those men and women who are able to get their asylum requests approved. There are hundreds of thousands of migrants in Europe whose applications have been refused, but who have not been deported. Many European countries lack the resources to deal with illegal immigrants, who end up working unofficially at the cash-in-hand jobs of the gray economy. Integration is also problematic; language barriers may prevent skilled immigrants from practicing their trade, and their children may struggle in school.

Moreover, every country faces unique demographic challenges; not all are equally willing to accept new immigrants. Low fertility rates and strong economies in countries such as Germany lead to more open immigration policies and the introduction of legislative reforms. But other nations, such as France and Finland, have relatively high fertility rates but stagnating economies and high unemployment, making immigration a politically sensitive issue and delaying reforms.

There are also countries, such as Greece and Portugal, which have extremely low fertility rates, high unemployment and weak economies. Governments in these countries may decide not to accept extra immigrants into their fragile economies, particularly when locals do not have jobs. Greece's situation also illustrates how a rise in immigration, combined with an economic crisis, can open the door for far-right groups to emerge, as is the case with the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party.

Meanwhile, many Central and Eastern European countries could actually benefit from immigrant labor to help bolster their populations. Nations such as Poland, Romania and Bulgaria will progressively lose population in the next four decades because of low fertility rates and high emigration rates. The region from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea faces a future where entire, largely rural, areas will be abandoned while young people emigrate and others move to urban centers looking for jobs. But elements within these relatively homogeneous societies may resist reforms to accept more immigrants. And even if Central and Eastern European governments can successfully open their borders to more immigrants, the region will struggle to compete with Western European countries that offer better salaries and education opportunities.

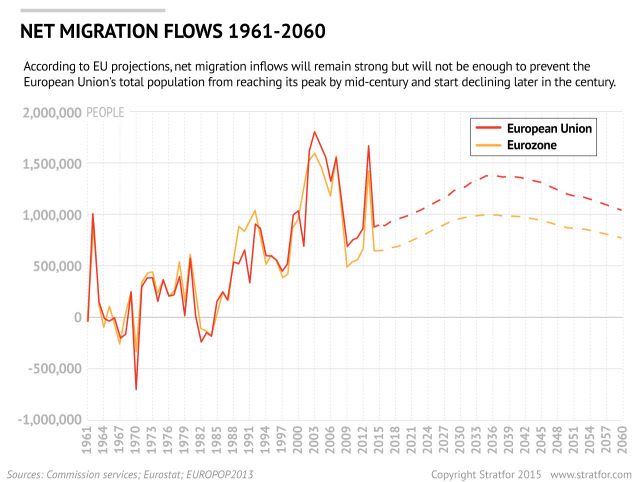

Each European country will react to these challenges in different ways. Evidence shows that immigration mitigates, but does not reverse, demographic change. Europe's population will peak by mid-century and then start to decline, even if immigration rates grow. Among immigrant families, which tend to have more children than their domestic peers, fertility rates are falling regardless. Though countries can institute policies to adapt to new demographics, there is little they can do to actually prevent change from happening.

Strategic Review has a content sharing agreement with Stratfor Global Intelligence.

resized.png)