Forecast

- The diverging interests of the participants in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) will probably prevent them from renegotiating the stalled trade deal.

- In the event that the TPP fails, some Southeast Asian states will shift their attention to reaching bilateral free trade agreements with the pact's members.

- Others will seek new trade partners elsewhere, diversifying their options by more closely integrating with their neighbors or tapping into consumer markets across the globe.

Analysis

Political leaders around the world are still taking stock of their options as U.S. trade policies evolve under the new administration in Washington. Perhaps nowhere is this more true than in East Asia, where, despite the almost certain demise of the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), several of its backers are continuing to try to save it. Some of the most stalwart supporters of the deal, which originally was intended in part to contain China's growing influence in the Asia-Pacific, have even brought alternative proposals to the table as they scramble to adjust their economic strategies to the wave of protectionism rising in the West.

But the hunt for new trade opportunities has also brought some Southeast Asian states to China's doorstep. Officials from the 16-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a Chinese-backed free trade framework that includes most TPP signatories in Asia, will head to the southern Japanese city of Kobe for negotiations on Feb. 27. Several TPP signatories, along with China and South Korea, will reconvene March 14-15 for talks in Chile's coastal city of Vina del Mar to mull their next steps in the wake of the TPP's failure. Similar to the TPP, the RCEP has been marketed as a multilateral framework for liberalizing and harmonizing certain standards among its participants. However, the pact has looser regulatory, environmental and trade requirements, and its exclusion of the United States has positioned China as the region's new rule setter.

.png)

Nevertheless, the downfall of the U.S.-led pact will not benefit China as much as it may seem. Most Southeast Asian economies don't have the luxury of choosing between ties with either Washington or Beijing. And, unable to weather threats of Western protectionism or trade spats brewing between Washington and Beijing, many have little choice but to hedge their bets by searching for new and more reliable partners elsewhere.

One deal for many agendas

Compared with the consequences of terminating the two-decade-old North American Free Trade Agreement, the fallout from calling off the TPP will be fairly limited. After all, the deal was never actually put into practice, and many of its perks — reduced tariffs, integrated supply chains and an uptick in cross-border investment, to name a few — would have taken time to materialize. Moreover, the deal's membership requirements carried their own risks for Asian members that would have had to enact contentious reforms in sectors they have historically protected. Vietnam, for instance, would have struggled to overhaul its labor unions without risking the government's hold on power, while Malaysia's attempts to restructure its pharmaceutical and auto industries would have met fierce resistance.

Of course there is still a chance, albeit a slim one, that the TPP will pull through. Should the United States rescind its rejection of the pact before the ratification deadline in February 2018, or should its 11 remaining members hash out a new version of the deal that they can all agree on, the trade bloc could yet survive. But neither of those outcomes will be easy to achieve, particularly since the original agreement took more than five years of torturous negotiation to craft in the face of its signatories' conflicting interests.

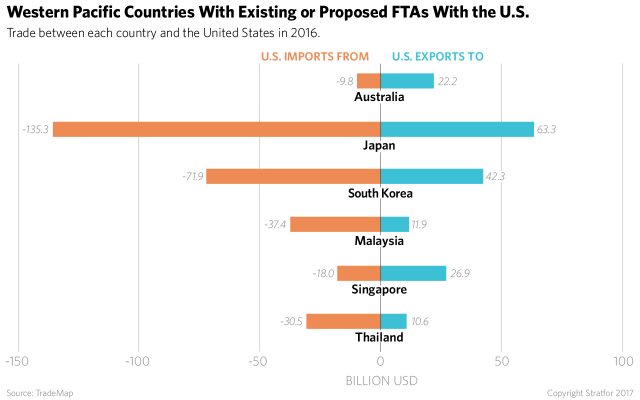

Those diverging aims have become even clearer as the TPP's participants struggle to adapt to a less open world. Some countries haven't given up on the prospect of maintaining a close relationship with the United States; for instance, Japan and South Korea (which is not a TPP participant) have moved quickly to meet U.S. President Donald Trump's "America First" agenda by promising to invest in U.S. infrastructure and manufacturing while shifting their balances of trade in Washington's favor. Japan, in particular, is determined to salvage the TPP, which it has long considered the linchpin to its own economic reforms and its defense ties with Washington as well as its ticket to a larger role in the Asia-Pacific region. Tokyo has lobbied for the United States to return to the deal, but it also has begun to pursue a bilateral free trade agreement with Washington in case the TPP cannot be revived. Singapore, with its high trade standards and existing free trade agreements with most of the TPP's members, including the United States, is also less than thrilled by the prospect of joining the pact without Washington. But with the TPP's prospects looking dim, neither Japan nor Singapore can afford to ignore the few other proposals for East Asian free trade zones on the table — most of which are dominated by China.

Australia and New Zealand, on the other hand, have advocated including China in the TPP in hopes of salvaging it. Chinese demand for raw materials fuel both countries' economies, and they are keen to reap the rewards of a multilateral free trade agreement involving Beijing. Meanwhile, Malaysia and Vietnam — arguably the states that stand to gain the most from the TPP, considering the sizable markets it would open for their raw materials and textiles industries — have kept fairly quiet on this proposal. Their reticence can largely be explained by their ambivalence toward Beijing and their lagging progress in enacting the TPP's required reforms on labor regulations, state-owned enterprises and intellectual property. Even so, both countries have stayed committed to meeting the trade pact's high standards while they search for other bilateral and regional free trade initiatives to spur their economic development.

Beyond the TPP's signatories, many Southeast Asian states have been somewhat relieved by the deal's collapse, in part because their low-cost manufacturing economies would be at a distinct disadvantage if the agreement were to survive. Cambodia's garment industry, for instance, may now have a little more room to breathe as it addresses rising labor costs and deteriorating infrastructure without heightened competition from Vietnam. The Philippines, meanwhile, has quickly shifted its attention away from the TPP and toward the RCEP, which would not only meet Manila's need to sustain its massive labor pool by lowering regional trade barriers but also support its diplomatic efforts to build closer ties with China. Finally, Indonesia — the largest economy in Southeast Asia — has recovered from the TPP's failure fairly easily. Its interest in the deal was primarily driven by the fear of losing out on access to the Vietnamese and Malaysian markets, rather than any broader strategic or diplomatic imperative. Consequently, it has contented itself with looking for other regional trade frameworks to fall back on. One of Jakarta's proposals, for example, is to create an alliance between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Mexico, Peru, Chile and Colombia that would counterbalance the economic clout of the United States and China.

Maintaining decades of momentum

At the core of these many solutions lies a simple truth: Southeast Asia is determined to maintain the momentum that has been building for decades behind the concept of free trade. Since the introduction of ASEAN's first preferential trading scheme in 1977, the bloc has gradually worked to prioritize economic growth and integration among its members, most of which are counting on exports to fuel their development. In 1991, ASEAN states signed an agreement that formed the foundation of the organization's free trade area. Nine years later, they struck a deal to form an investment area aimed at encouraging the flow of foreign funds into all of the region's biggest industries. To date, Southeast Asia remains one of the regions with the most free trade agreements in the world.

Part of ASEAN's success stems from its diverse membership. The bloc's framework gives the region's small economies a way to form a united front — and amass more bargaining power — in negotiating trade and investment deals with more powerful partners. But its consensus-based approach to decision-making makes it more difficult for ASEAN to reduce tariffs or raise trade standards among its members, which each face unique socio-economic realities and employ different styles of governance. The organization's members, moreover, tend to export similar products such as raw materials and finished manufactured goods, limiting the amount of intraregional trade the bloc's free trade agreement can actually encourage. As a result, many ASEAN states with sturdier economic foundations have sought out trade avenues beyond the confines of the bloc.

Their search has only intensified as the TPP has fallen apart. Many of the pact's Asian members have begun to explore or fast-track bilateral trade opportunities with their fellow TPP signatories. Malaysia, for instance, has set its sights on signing free trade deals with the United States, Canada, Mexico and Peru, while Vietnam has turned its gaze to the United States and regional trade blocs such as the European Union and Eurasian Economic Union. But building new bridges to the U.S. market will not be easy for these countries, especially since Trump has made it a point to deprioritize trade with partners with large trade surpluses and low-cost manufacturing industries. This could also complicate Thailand's attempts to resume its long-delayed free trade talks with the United States, which will doubtless include thorny issues regarding automobile and agriculture trade, the protection of intellectual property and customs regimes. Meanwhile, more advanced economies that already have free trade deals with the United States, such as Singapore and Australia, may see their existing agreements adjusted to include greater scrutiny on labor regulations and environmental standards.

The only option: finding new options

The United States' withdrawal from the TPP is by no means the only thing encouraging Washington's Asian partners to pursue other trade opportunities. The gradual recovery of global commodities prices and demand has brought welcome relief to many of the region's major exporters, including Australia and Indonesia. But the risks that a slowdown in China's housing sector, protectionism in the developed world and a brewing Sino-U.S. trade war pose to these countries' economies are still very real.

Of course, unlike China, Japan and South Korea, most Southeast Asian states aren't in the direct line of fire of Washington's protectionist policies. But as one of the largest trade partners to China and the United States, the region has become an integral part of both countries' ever-growing supply chains. (In fact, some Southeast Asian states are well positioned to act as substitute suppliers of textiles and electronics if Washington enacts punitive tariffs against Chinese goods.) And as demand in the two major consumer markets of the East and West threatens to shrink, their Southeast Asian suppliers will be forced to protect themselves by diversifying their options, whether by finding new markets for their exports or expanding their own industrial value chains.

Strategic Review has a content-sharing agreement with Stratfor global intelligence.

resized.png)