An electoral system functions not only as a procedure and mechanism to convert votes into seats within legislative bodies, but also as a set of instruments for democratization of a political system. As it did in the 2009 national legislative election, Indonesia will apply a proportional electoral system to elect members of the House of Representatives and at the provincial and district level in its 2014 polls. Hence, what kind of democratic political system results from proportional elections?

In this essay we will see that Indonesia’s current system is deeply flawed and that proportional representation, the timing of elections and a confused presidential system are having a negative impact on democratic development.

The following is a description of six elements of an electoral system and its consequences on various aspects of Indonesia’s political democracy.

District size

The system established by the 1945 Constitution can be categorized as almost bicameral. Aside from the House of Representatives with legislative authority, there is also the Regional Representatives Council, which represents the country’s regions. The allocation of 560 seats in the House of Representatives, or DPR, from Indonesia’s 33 provinces is based not solely on the size of the province’s population, but also on the balance of representation between Java and the other islands (each province is represented by three seats at a minimum), as well as political lobbying in the national legislature. The balance of representation between provinces still affects seat allocation in the DPR, as the authority of the Regional Representatives Council is deemed unequal to that of the national legislature.

The 560 members of the House are elected in 77 constituencies, 39 of which are in six provinces within Java, competing for 306 seats (55 percent). There are 38 constituencies in 27 provinces outside of Java competing for 254 seats (45 percent). By looking at the House of Representatives’ seats allocation, it’s obvious that it does not reflect equal representation. Provinces that are categorized as “underrepresented,” where one seat equals between 430,000 to 560,000 citizens, include Riau Islands, Riau, West Nusa Tenggara and North Sumatera; provinces that are categorized as “overrepresented,” with one seat equaling 255,000 to 354,000 citizens, include West Papua, Papua, Aceh, West Sumatra, North Maluku, South Sulawesi, Gorontalo and East Nusa Tenggara, all outside of Java.

What are the consequences of the size of constituencies and the distribution of seats in the House of Representatives? As many as 70 out of 77 constituencies in the House can be categorized as medium multi-member ones, as they have between six and 10 seats. The size of a constituency ensures both the level of representation and also the opportunity for small to medium-sized political parties to obtain seats. Which political parties will obtain more seats? For provinces within Java, as well as a number of underrepresented provinces outside of Java, obtaining seats is more challenging compared to constituencies in Outer Java, in particular overrepresented provinces.

Participants and the pattern of candidacy

Indonesia applies an irregular mechanism to determine political party eligibility. Ideally, all political parties, both those that meet the electoral threshold for the DPR and those that do not, should be able to participate in the next election. These parties should not have to undergo the verification process as election participants; only new political parties need to do so. However, Article 8 of Law Number 8/2012 on Legislatives Election stipulates that new political parties and existing parties that fail

to meet the threshold for the House must again undergo the verification process. As a consequence, 29 political parties that failed to meet the electoral threshold in 2009 filed a petition to the Constitutional Court to annul Article 8. The court agreed and even ordered that all political parties which participated in 2009 (including the nine political parties that met the threshold and won seats) would again undergo the verification process for the April 2014 election. Based on the verification process, conducted across all of Indonesia’s 33 provinces, Indonesia’s General Elections Commission (KPU) approved 12 political parties to participate in this year’s poll.

There are two differences between the 2009 election and this time around. First, there was external pressure on political parties to consolidate much earlier – in particular the decision by the Constitutional Court requiring all political parties to redo the verification process. Second, the number of parties contesting the 2014 election is far lower than in 2009, when 38 were involved. Will this have political implications on the quality of political parties and their opportunities to secure seats?

Indonesia’s proportional electoral system contains inconsistencies between candidacy patterns and the determination of candidates. Pursuant to the 1945 Constitution, which designates political parties as the main contestants at the House of Representatives and provincial, district and municipal level, the election law requires them to submit lists of proposed candidates based on a party list. The list means two things: the political party develops its list of proposed candidates based on set criteria and therefore a small number of people are considered the best candidates; and a candidate’s rank determines if they enter parliament based on the number of seats won by their party.

Further, the election law mandates that 30 percent of candidates in each district be women. However, although the law obliges political parties to meet the quota for candidates and women candidates in all constituencies, it does not explicitly stipulate sanctions for parties that fail to do so. To address this gap, the election commission issued regulations stipulating administrative sanctions against political parties that fail to meet the quota.

There are at least two aspects in the candidacy pattern and policy on quotas for women that require our attention. First, will the quality of House members improve from 2009 in terms of personal integrity and capacity to carry out legislative duties? Nine political parties will account for around 80 percent of incumbents running for re-election. In 2009, incumbents accounted for only 35 percent. It is interesting that most of the current House members, as well as new candidates for 2014, were not selected through structured recruitment and cadre development. Since most only joined in 2009, and because the majority of candidates this year are incumbents, will their performance be better than lawmakers who were elected in 2004?

It has been shown that House members elected in 2004 were more productive in developing legislation and had a higher attendance rate compared to those elected in 2009. Considering that most members elected in 2009 will likely be re-elected, it is too optimistic to hope for improved performance from members elected this year – unless voters choose high-quality candidates. Second, will the percentage of women increase compared to 2009? The answer depends not on their campaigns, but on voting behavior. Will voters, as occurred in 2009, cast their votes for candidates sitting at the top of the candidacy list?

Balloting model and vote equality

The balloting model adopted in the current election law contains inconsistencies. Voters are required to cast votes for one political party and/or one candidate. Votes cast for a candidate will automatically be counted as one vote for him or her and one for the political party they represent. However, a vote cast only for a party will not determine the winning candidate; the vote will only determine the seat for the party. In other words, voters who cast their votes in accordance with the 1945 Constitution, which designates political parties as the election participants and not individuals, will get a “half vote,” while voters who cast ballots for a candidate get “one full vote.” This contravenes the “one person, one vote” principle since the value of votes cast for a political party are unequal to votes cast for candidates.

Proportional with plurality of votes

There are at least three methods to allocate seats based on the Proportional Representation formula: the Hare quota with the largest remainder method to allocate seats, which tends to benefit small parties; the D’Hondt method, which tends to benefit major parties; and the Sainte-Lague method, which is the most fair due to its neutrality to party size. Indonesia applies the Hare quota, which is more beneficial to small parties. The preferred formula also contains inconsistencies under the frame of a proportional electoral system. On one side, one of the purposes of the election law is to reduce the number of political parties (through, among other things, a 3.5 percent threshold to enter parliament). However, this preferred formula opens opportunities for small parties to secure seats.

The most striking inconsistency in Indonesia’s proportional electoral system is between the determination of winning candidates and candidacy patterns. The winning candidates are determined based on the number of votes, while candidacy pattern is based on the candidates’ number on the party list. Hence, legally the listing of candidates based on criteria established by the parties and the quota policy of women being 30 percent of candidates and having at least one female for every three candidates on the party list in a district, are ineffective. Nevertheless, empirically, candidacies based on list number and quota policy and the small-number quota policy for women were effective in the 2009 election, since votes for candidates with a low number. Whether the pattern will be similar in 2014 will primarily depend on the behavior of Indonesian voters.

The quota method and the largest remainder method tend to benefit small parties. Political parties that are unable to garner votes equal to or more than the quota are also categorized as remaining votes. Therefore, it is not surprising that a political party that garners more votes than other parties may only obtain an equal number of seats, and this is why the quota and largest remainder methods tend to benefit small parties. However, to secure a seat in the House of Representatives, a political party must meet the voting threshold of 3.5 percent of the votes, hence the quota and largest remainder methods tend to maintain a large number of political parties participating in an election – unless, political parties that fail to meet the threshold are also obliged to go through the verification process again.

How to buy votes

What is the effect on the quality of elected members and women’s representation of determining winning candidates based on the plurality of votes? Several factors influence the answer to this question. If all political parties determine their party list based on strict and measurable criteria, then a candidate in first position would be the “best” candidate, the second candidate would be second best and so forth. The second factor relates to voting behavior. If voters tend to choose candidates at or near the top of the list, the elected candidates should be suitable according to the parties’ criteria and should also mean an increase in the number of women elected, or at least the same amount chosen in 2009. However, if voters don’t cast ballots for candidates at or near the top of the list, then winning candidates will not be the ones who met the parties’ criteria and the number of elected women will be lower than in 2009.

Of the two possibilities, the first is more likely. Voters will likely cast their votes for candidates at the top of the list not only because they are the “best” but also because voters avoid complicated means when they cast ballots. Choosing one among at least 36 candidate names in a constituency that has three seats, for example, is a difficult task for most voters.

What is the consequence of determining winning candidates based on the plurality of votes in terms of electoral malpractice, especially vote-buying? Determining winning candidates based on a plurality of votes with a constituency of between six and 10 seats creates opportunities for vote-buying. The formula provides two types of incentives for candidates and voters. First, votes become a tradable commodity: the candidates need votes to win, voters own the commodity and polling officials have the authority to sign voting documents and count results.

Second, the number of votes required to win is not substantially large since candidates do not need a simple majority. If a political party manages to secure two seats, the seats will be granted to candidates who garner the first and second highestnumber of valid votes.

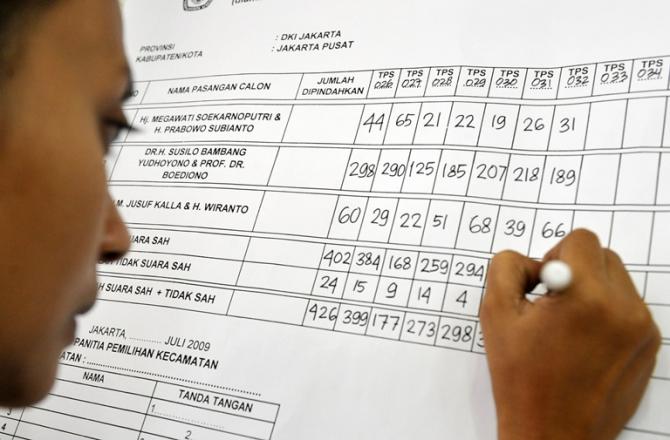

Based on 2009, there are at least five ways to go about vote-buying. First, a candidate may buy votes directly from voters, either individually or collectively, through a middleman who is usually a familiar person among the voters. Second, a candidate may “buy” votes from other candidates within their party and within the same constituency. The buying candidate is typically someone who requires extra votes in order to win, while the candidate who “sells” them does not have enough to win anyway. The buying candidate usually will reimburse the campaign expenses of the selling candidate. Vote-buying can only occur with approval from polling officials and/or election officials at the subdistrict level, with the excuse that it’s a party’s internal issue, irrespective of whether bribes are involved.

Third, on polling day, a voter may vote for one party, or candidate, or a party and one of its candidates. Hence, the party would garner votes not only for candidates but also direct votes for itself. Votes garnered by a party may be “taken over” by one or more candidates who need extra votes to get in. The vote takeover may only occur with approval from polling officials and/or election officials.

Fourth, candidates who still need more votes may steal votes from other candidates from the same party and constituency. Vote-stealing may occur with approval from polling officials and/or election officials at the subdistrict level, upon receiving an “appreciation fee” from the stealing candidate. If this method is exposed, candidates whose votes are stolen will protest since the loss of the votes damages their chances to win a seat.

Fifth, a candidate from a political party buys votes from one or more other political parties within the same constituency. The selling parties are typically small and will not get enough votes to secure a seat. Vote-buying via this method may only occur after subdistrict level polling officials and/or election officials receive bribe money.

Threshold for the DPR

The threshold to enter the DPR is 3.5 percent of the total vote for members of the House of Representatives. The purpose of the threshold is to reduce the number of political parties in the House. Will it achieve its purpose? Out of 12 political parties participating in the 2014 election, how many will meet the threshold? I raise these questions because there are three elements in Indonesia’s electoral system that have counter effects. First, the range of constituencies is considerably wide since 70 out of 77 constituencies have between six and 10 allocated seats. The higher the number of seats in a constituency, the higher the opportunity for small parties.

Second, the proportional electoral formula uses the Hare quota method, while the remaining seats allocated to political parties is based of the largest remainder. This formula tends to benefit small parties, as parties whose votes do not meet a quota still have the opportunity to secure seats.

Third, the DPR election is held three months prior to the presidential election. Consequently, during the election period, voters generally do not consider presidential candidates in determining their choice (although when a particular candidate is known to be running for a given party it can impact on voters’ decisions, as clearly happened in 2009 when President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was the obvious choice for his Democratic Party). Presidential candidates don’t officially exist at that time and voters are presumed to cast ballots based only on a party’s characteristics. This enables high numbers of political parties to win seats in parliament. If the 3.5 percent threshold is applied along with the limited size of a constituency of three to six seats, the preferred formula for proportional electoral system is the Sainte-Lague method, and if the election is held on the same date and at the same polling place, the number of political parties in the parliament would be more manageable.

Non-concurrent elections

The timing of elections also affects the quality of a democratic system. Based on amendments one through four of the 1945 Constitution, Indonesia has been holding three elections separately. Legislative elections (House of Representatives, Regional Representatives Council, and provincial and local lawmaking bodies) are held in the first week of April, once every five years. Meanwhile, the presidential election is held in the first week of July, once every five years and three months after legislative elections. Elections for regional leaders including governor and district chief are held throughout the year.

The election schedule brings results that not only run contrary to the policy to reduce the number of political parties in the House, but also with the presidential system of government as stipulated in the 1945 Constitution and with the purpose to create political parties that are accountable to their constituents. Holding legislative elections three months before the presidential election not only enables large numbers of political parties to win seats in the House, but also promotes a legislature with characteristics similar to a parliamentary system rather than a presidential system.

Non-concurrent elections for the president and members of the House create less effective presidential governance. In addition, non-concurrent elections means voters only have an opportunity once every five years to evaluate and appraise the performance of political parties and governments.

Deficits in a democratic political system

The proportional electoral system in Indonesia contains a number of contradictions or inconsistencies. First, with 70 out of 77 constituencies having six to 10 allocated seats, the result is medium-sized, multi-member constituencies. This size of a constituency is believed to foster the presence of large numbers of political parties in the House of Representatives. However, there is a 3.5 percent threshold to gain membership in the House – a regulation specifically set to reduce the number of political parties in the DPR.

Second, the medium multi-members constituency is designed to ensure an adequate degree of representation. However, the voting mechanism and determination of winning candidates based on the plurality of votes would not only nullify the role of political parties as election participants, but most importantly would steer political representation into efforts to ensure accountability of the people’s representatives. On paper, the political representation system would shift from promoting representation of the people to promoting the representatives’ accountability.

Third, the candidacy pattern is determined based on party list, but winning candidates are determined based on an open list. Despite election law requirements that political parties shall utilize their vision, mission and programs as campaign material, the campaign is practically carried out by the candidates themselves, who garner votes using whatever means they choose. Hence, what occurs is not competition between political parties; instead, the competition is between candidates from the same political parties, within the same constituency. The result is that political parties are like event organizers rather than true participants in an election. Hence, the question arises of who is representing the constituents: the winning candidates or the political parties? If the representatives are the winning candidates, then why is decision-making in the House of Representatives made by party leaders who push the parties’ policies?

Fourth, in order to increase women’s representation in parliaments, a number of democratic countries with proportional electoral systems adopt quota policies for women, but also use similar candidacy patterns and mechanisms to determine winning candidates via a party list. However, in Indonesia, the opposite applies. Although political parties are obliged to have at least 30 percent female candidates in each district and at least one woman for every three candidates on the party list in each district, winning candidates are determined based on the plurality of votes. As a consequence of this inconsistency, candidate quotas and small-number quota policies for women become void. The increase of elected women as members of the House in 2009 was not the result of the electoral system but due to Indonesian voters, who tend to vote for candidates listed first, second or third on a ballot.

Fifth, the 1945 Constitution mandates political parties as participants in the legislative elections, but votes for election participants are valued less (as the votes only help securing seats for political parties) than votes cast for candidates (which help secure not only seats for the party but also for the candidate). This mechanism certainly contradicts the one person, one vote, one value principle as stated in Article 27, Paragraph (1) of the 1945 Constitution, since the value of votes for parties is unequal to the value of votes for candidates.

Sixth, to reduce the number of parties in the parliament, a 3.5 percent threshold was created. However, at the same time, the election law adopts three elements of an electoral system that enables political parties to secure seats. The three elements are: size of a constituency, a proportional electoral formula using the Hare quota method while outstanding seats are allocated to parties based on remaining plurality of votes, and an election calendar that has three months between the legislative and presidential elections.

Seventh, even though Indonesia has a presidential system, its legislative election is held prior to the presidential election. Political parties turn into political event organizers, while candidates run as election participants. As the role of election participants shifts to candidates, party discipline decreases (elected candidates feel more legitimate than the parties).

To have an effective presidential system, presidential and legislative elections need to be held simultaneously so that a president’s policies contribute to the development of a moderate pluralist party system. At the same time, party discipline needs to improve. What we are witnessing today is two government systems: political parties showing parliamentary behavior in the legislature and presidential behavior within the executive.

Aside from containing a number of inconsistent elements, the proportional electoral system potentially lures candidates, voters and/or election officials to be involved in vote-buying. If money is used to gain a position then that position will one day be abused to seek monetary gain.

Indonesia’s proportional electoral system contains contradictory elements that help create a deficient democratic political system. First, the focus of political parties (and their candidates) is to seek and maintain power through election, including through vote-buying, rather than by performing their functions as political representatives. Furthermore, political parties both internally and externally lack democratic management. In the end, parties should not only be accountable to their members but also their constituents.

Second, political representation is not effectively carried out due to the question of who represents the constituents: political parties or members of the House. As a result, political parties and winning candidates perform only formal representation roles while civil society organizations, for example, perform substantive ones.

Third, there is uncertainty regarding unicameral and bicameral political representation, as well as uncertainty between people’s representation and representatives’ accountability.

Fourth, many political parties in the House of Representatives behave as if Indonesia has a parliamentary system, and President Yudhoyono, as the leader of a presidential system, is overwhelmed by political pressure within the DPR. The president’s ruling Democratic Party controls only 26 percent of seats, so to gain necessary support for his policies, Yudhoyono created a cabinet where half of the 34 positions are held by members of a six-party coalition. Yet since the 2009 presidential election, the coalition’s leadership is more transactional than transformative. A number of political parties whose members hold ministerial posts in the cabinet (not including the Democratic Party) oppose government policies more often than the three political parties in the formal opposition. In effect, it is not uncommon for the government to be divided, not only executive versus legislative but also the president versus ministers from other political parties.

Fifth, the presidential system at both the national and regional levels is not effective, and as such the public has not seen significant results. There are at least two indicators of effective presidential government: public policies agreed by both the president and the House that reflect the people’s interests, and the implementation of those policies. Ineffective presidential governance occurs not only because Yudhoyono has not had solid support from the House of Representatives, but also because his political leadership has not been successful in harvesting support from all elements of civil society – as well as the 61 percent the electorate that voted for him in 2009.

Last but not least, people power is still theoretical rather than a reality. Political parties participating in elections and appointed government officials are not accountable to the people. Furthermore, the people have not had proper access to demand accountability and public political participation is still extremely limited. Notably high participation in elections is a prerequisite, but that alone will not suffice. An electoral system should also ensure as much access as possible for voters to influence political parties and elected officials after elections, and also reward those who fulfill their campaign promises by re-electing them and punishing those who do not.

Once every five years may not be adequate for this. Voters need access and opportunity to appraise political parties and government officials and demand accountability, and either reward or punish them. Among other things, this is what Indonesians are lacking.

Ramlan Surbakti is a professor of political science at the School of Social and Political Sciences at Airlangga University in Surabaya.

resized.png)