With the successful 2014 legislative and presidential elections well in the rearview mirror, Indonesia’s new government can now tackle issues of governance, a key one being effective and efficient policy coordination and consultation.

Effective interministerial policy coordination and policy consultation (PCC) can help eliminate policy programs that duplicate actions and regulations. PCC is a necessary element to deal with cross-cutting issues of policy-making in developing countries including Indonesia. Deficient policy coordination and policy consultation decreases a country’s ability to ensure the sustained development of its economy and society, and can handicap its success in reaching beneficial agreements through bilateral and multilateral negotiations.

The world faces new challenges: climate change, migration, financial instability, refugees, conflict and war, unemployment and diminishing job prospects for young people. There needs to be a fast, concerted and competent response to these multiple challenges, which are interconnected and require global and local solutions. In other words, they require effective and efficient policy coordination and consultation from a multidisciplinary perspective.

Increasing economic competitiveness, for example, can only be achieved through better policy coordination and strengthened value chain integration. Since different elements of the supply and value chain are linked to different government ministries, the mechanism and practice of interministerial policy coordination becomes crucial to ensure successful policy implementation. Without successful interministerial policy coordination, ministries will not harmonize their policies and a comprehensive value chain approach cannot be implemented.

Of equal importance are effective policy consultations with non-state stakeholders that have either offensive or defensive interests in a specific sector. For example, trade policy affects stakeholders that are active in a specific sector (e.g., enterprises, professional associations, educational institutions) as well as stakeholders representing social sector organizations such as labor unions or nongovernmental organizations. These non-state actors have offensive and defensive interests, seeing themselves as winners or losers of a new policy that might aim at the structural adjustment of an economic sector. A government has to find the right measures to consult, involve, inform and negotiate with these non-state actors as it goes through the phases of policy-making such as policy initiation, policy formulation, policy implementation and policy evaluation and monitoring.

This essay discusses the current situation of Indonesia’s trade policy coordination and policy consultation, and the accompanying problems. The authors argue that there is a transparency issue due to an unclear reporting and authority mechanism under the current system. In this regard, the Indonesian government risks conducting ineffective, inefficient and unpredictable policy processes. This essay also provides an alternative option to the current Indonesian governance structure by exploring the multi-stakeholder policy process of Switzerland’s financial policy sector. The Swiss example gives a detailed overview of how the Swiss government has organized mechanisms of interministerial policy coordination and consultation with external stakeholders, in order to cope with the many external and internal changes of the financial sector, which is of great importance to the Swiss economy.

Case examples

A study by Arfani and Winanti (2014) showed Indonesia as having successfully diversified its natural resource development into the tradable manufacturing sector. The study argued that Indonesia’s next challenge was to further diversify its exported commodities, notably by moving up the value chain in established sectors of activity. By focusing on three broad industry categories – the mining industry (with specific reference to coal and copper); the oil and gas industry; and the plantation industry (with specific reference to palm oil, rubber and paper-related industries) – the study emphasized that Indonesia’s trade is characterized predominantly by the export of natural resources and raw materials, which use little foreign value-added content.

In other words, the domestic value-added content of Indonesia’s exports is still high. Given the current context, Indonesia faces the challenge of upgrading within established value chains or diversifying into new value chains. Facing this challenge requires sound interministerial policy coordination and government policy consultation, with stakeholders including business and civil society.

A clear example of how interministerial policy coordination is crucial comes from derivative regulations on domestic market obligations and export restrictions on the mining industry, which were designed in line with the government’s downstream strategic plan to generate more domestic value-added activities. On the one hand, these policies may have constructive implications for Indonesia’s wider energy sector sustainability and electrical power supply needs, as they increase the possibility of initiating a functional, intersectoral upgrade of the coal industry, thereby releasing it from lower value-added production and processing (Arfani and Winanti, 2014). On the other hand, achieving targeted policy goals also depends on the Indonesian government’s plans to further encourage investment in domestic smelters.

In the case of the oil and gas industry, the promulgation of a 2001 law has offered a new perspective on the sector and the dimensions to upgrade, diversify and introduce other value-addition activities within the sector. Significant changes introduced by this law relate particularly to business and commercial relations between state-owned enterprises such as Pertamina, the national oil and gas company, and multinational corporations operating in Indonesia.

Inadequate and uncoordinated horizontal policies within the plantation industry have resulted in severe structural problems. The palm oil sector has long been hampered by constraints arising from issues such as forest destruction, environmental degradation, land use, land pricing and the tenure system, low wages, industrial practices and other social and environmental problems. The industry also has been characterized by disputes and discordant relations among smallholder producers, large producers and surrounding communities. Dealing with this issue clearly requires rigorous interministerial policy coordination and government policy consultation with stakeholders, including businesses and civil society (Arfani and Winanti, 2014).

The Indonesian government’s structure

Indonesia’s current government structure is highly complex. There are 34 ministries, four ministerial-level governmental agencies and 29 non-ministerial agencies, as well as more than 500 provincial, district and municipal governments. The overall organogram gives indications of hierarchical order but appears at times to be very informal, as no direct reporting lines are indicated. To manage the complexity, the current structure provides four coordinating ministers, namely:

• Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs (Minister Tedjo Edhy Purdijatno)

• Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs (Minister Sofyan Djalil)

• Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs (Minister Indroyono Susilo)

• Coordinating Minister for Human Development and Culture (Minister Puan Maharani).

All four coordinating ministers, the state secretary and the national development planning minister are part of President Joko Widodo’s working cabinet.

The organizational structure of the Indonesian Cabinet

Source: http://indonesia.go.id/in/kabinet-kerja/

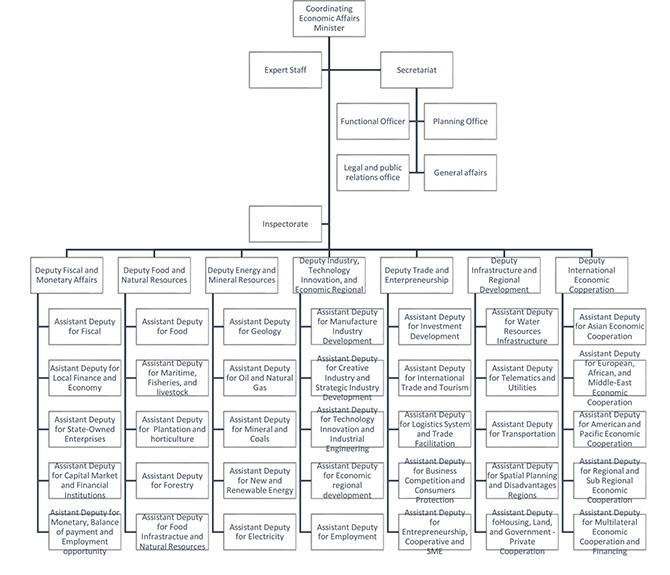

Chart 2 (below) shows how policy coordination has been conducted under the coordinating minister for economic affairs. The following organization structure is based on a 2012 regulation that has not yet been changed by Joko’s administration.

The organizational structure of the Indonesian Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs

Source: http://indonesia.go.id/in/kabinet-kerja/

Furthermore, the coordinating ministry’s expert staff consists of:

1. Expert staff for politics, law and security

2. Expert staff for social welfare and poverty reduction

3. Expert staff for human resources, science and technology

4. Expert staff for local development

5. Expert staff for climate change

6. Expert staff for national competitiveness enhancement

7. Expert staff for communication and information

By not making reporting and authority lines visible and transparent, the Indonesian government takes the risk of ineffective, inefficient policy processes that lack a systematic, predictable and, hence, politically more acceptable policy approach. The system could become prone to informal arrangements, which often leads to rent-seeking behavior.

The Switzerland model

Policy coordination and policy consultation are organized differently from one country to another, often because of historical reasons and due to political compromise arrangements, especially within a multiparty coalition government. As a way to reflect on alternative options to Indonesia’s current governance structure, an example is given below from Switzerland.

To defend its economic and financial interests, and to contribute to the solving of international financial problems, Switzerland has tried, unsuccessfully, to become a member of the G-20 in order to promote its financial sector. According to the Swiss Bankers Association, the financial sector is the largest contributor to the country’s economic development, generating more than 12 percent of gross domestic product, accounting for between 12 percent and 15 percent of tax revenues and providing 195,000 skilled jobs. In this context, the most relevant topics supported by Switzerland at the G-20 are the reform of the international monetary system, the strengthening of financial regulations and measures addressing development, employment, corruption, governance and the volatility of commodity prices. Switzerland has participated in preparatory meetings held by the G-20 and has actively contributed to international organizations entrusted by the G-20 with implementation tasks.

The multi-stakeholder process of Switzerland’s financial policy sector strategy involves four main bodies: the Swiss National Bank, the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, the Federal Department of Finance and the Federal Department of Economic Affairs. Each of the three ministries has a division or a secretary that leads the consultative process vis-à-vis certain international organizations. Within the foreign affairs department, the United Nations and International Organizations Division coordinates and implements Swiss policy regarding the UN, its specialized agencies and other international organizations. The State Secretariat for International Financial Matters at the finance department is responsible for Swiss relations with the International Monetary Fund, and the economic department’s State Secretariat for Economic Affairs is responsible for Swiss relations with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Matters pertaining to Switzerland’s relations with the G-20 are coordinated through the Inter-Departmental Working Group G-20. IDAG20 is a working group composed of the state secretariats of the departments of economic affairs and finance, the foreign department’s Directorate of Political Affairs and the Swiss National Bank.

They meet four to five times a year. Notably, there is no formal document regulating Switzerland’s interministerial and interinstitutional coordination process. The IDAG20 is coordinated by two federal offices, which alternate chairing the working group from one G-20 presidency to the next. Other actors are also informed as required, and there are sectoral consultations on trade, finance, labor and fighting corruption.

These different actors are consulted by government authorities to base financial policy on broad political support.

Switzerland´s consultative process: Inter-Departmental Working Group G20 (IDAG20).

.jpg)

Source: Saner, R, paper prepared for the Lowry Institute, Australia in preparation of 2014 G20 meeting.

Moreover, the interministerial working group interacts with different state and non-state actors that are involved in shaping Switzerland’s financial policy and economic diplomacy. These actors are:

• The Swiss Financial Supervisory Authority, an independent supervisory authority that protects creditors, investors and policyholders, ensuring the smooth functioning of the financial markets

• The Swiss Bankers Association, a professional organization to maintain and promote the best possible framework conditions for the country’s financial center

• Economiesuisse, a leading lobbying group of Swiss industries

• Alliance Sud, a pressure group of leading Swiss involved in development assistance

• The Finance and Foreign Affairs committees of the two parliamentary chambers of the Swiss Federal Assembly

• Swiss media and political parties.

Mechanisms for Indonesia

Policy coordination and policy consultation mechanisms offer varying degrees of policy governance, ranging from a heavily decentralized to a heavily centralized structure. The form of governance must provide the most effective and efficient manner of managing the following aspects of national policy-making:

1. Supporting national development strategy

2. Linking related policy sectors in a synergistic way

3. Providing means to implement international commitments

4. Giving support for the conduct of international negotiations

5. Offering an optimal balancing of the interests of key national stakeholders

6. Ensuring swift implementation of national policies.

The graph below shows the different governance mechanisms available to a government, depending on its priorities, of course, but most important on its assessment of how it can ensure efficient and effective policy coordination and policy consultation.

Source: CSEND 2009

After each renewal of a government subsequent to elections, the ensuing grace period should be actively used to reassess the current functioning of the government and to redesign the structure and functioning of the government, including reassessing what competencies (skills, knowledge, attitude) are needed to ensure the effective and efficient performance of civil servants.

Institutional reform might be useful to ensure effective and efficient PCC. Such reforms could, for instance, include the following measures: a) improving the use of policy tools, communication strategy and implementation; b) monitoring and evaluating PCC; c) improving the coordination mechanisms of the legislative departments of line ministries; d) auditing and improving financial flows, budgeting and responsibility assignments; e) reassessing the effectiveness of the record-keeping practices of ministries (criteria to designate what should be confidential and what could be made available, both within the government and among the public at large). All of this strengthens a government’s commitment to provide services to economic actors and citizens in a nondiscriminatory, transparent and accountable manner.

Conclusion

Effective and efficient policy coordination and policy consultation are crucial to ensuring sustained economic growth and sustained and balanced social policies. The example given in this essay pertains to trade and external and internal value chain integration. Since different elements of the supply and value chain are linked to particular Indonesian government ministries, policy mechanisms are needed to strengthen interministerial policy coordination and make policy consultation between the government and economic and civil society organizations transparent, predictable, nondiscriminatory and accessible to all stakeholders.

Without successful policy coordination, Indonesian government ministries will not be inclined to harmonize their policies, and a comprehensive value chain approach cannot be implemented. Without sustained and effective policy consultation, important stakeholders with offensive and defensive interests in current and future policy changes might feel excluded and revert to illegitimate forms of influence that could result in bribery, deceit and duplicitous maneuvers to outdo other stakeholders opposing their interests. The can lead to conflicts that bind the government’s energy and resources, rather than giving it the space and trust required to move the country forward.

Whatever is decided on the structure of policy coordination and policy consultation, there should be a formal component and a convening agency to oversee the process of interministerial policy coordination and consultation between the government and the private sector/civil society. Without appropriate structures and adequate coordination and consultation mechanisms, a government is prone to deficient decision-making and paralysis in policy implementation.

Indonesia could benefit greatly from effective and efficient policy coordination and policy consultation, and hopefully the new government will select the right mechanisms to support the implementation of its development strategies and priorities.

Raymond Saner teaches at Basel University in Switzerland and is co-founder of CSEND, a Geneva-based research and development organization.

Poppy S Winanti is head of the graduate program in international relations at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta.

%20resized.png)