JOURNAL | INDONESIA 360 by: Ian Buchanan

On Oct 20, 2014, in an atmosphere charged with enthusiasm, optimism and hope, Joko Widodo was inaugurated as Indonesia’s seventh president. The optimism was most evident among his young, digital-savvy supporters who during a closely fought election used their smartphones to combat fraud by capturing and tallying nationwide voting results.

Joko’s own enthusiasm and optimism – he is Indonesia’s second-youngest president – combined with a strong track record as mayor of Solo, in Central Java Province, and then as governor of Jakarta, further raised expectations of positive changes during his first 100 days in office. Today, approaching the end of his second year in office, an older and wiser president, facing the realities of Indonesia’s complex national and regional politics, weak and bureaucratic institutions, and a deeply rooted political patronage system, is moderating his short-term promises and moving to build alignment around a unifying, long-term vision (or impian) for the nation, out to the year 2085.

The vision includes developing world-class human capital; creating an internationally influential nation that values pluralism; being a global center of education, technology and civilization; zero corruption; building quality infrastructure; and having a globally integrated economy.

The president’s detractors will no doubt argue that a vision (or dream) set almost 70 years in the future does nothing for Indonesia’s rakyat (people) today. While it may seem counterintuitive, I will draw on lessons from my involvement during the past four decades with a variety of national change programs in the region to argue that a national vision can be the right starting point – but only if it meets two conditions: the vision must be widely shared with and supported by the public; and there must clear, measurable and trusted short-term milestones against which progress toward the vision can be measured.

On the first prerequisite, while President Joko may lack experience, he is a gifted and persuasive orator. It will be essential that he invests the time and effort to build understanding and consensus on his impian. Two young role models whose visions and words created great nations might include Soekarno, who on June 1, 1945, at the age of just 43, forged the foundations for modern Indonesia with his vision of one independent nation built on the five shared principles of a new state philosophy, Pancasila. Joko may also draw lessons from Kemal Ataturk, the father of modern Turkey, who at the age of 46 delivered his famous “Nutuk” speech to Parliament between Oct. 25 and 29, 1927, which offered his far-reaching vision for his war-ravaged nation.

On the second prerequisite, Joko has already proposed a metric that many best-practices countries are already using: the World Bank’s “Doing Business” index. This trusted, independent, annual and public index offers “league tables” of the performance of 189 countries (Indonesia is currently 109, the third-lowest in Southeast Asia), combined with in-depth country reports on the underlying drivers of the rankings, and what can be done to improve them. The index provides comparable, quantitative metrics on a wide range of measures of regulatory complexity and transparency, including ease of starting a business, property rights and access to credit, to deliver short-term progress toward Joko’s long-term impian.

While the World Bank report does not specifically include corruption, collusion and nepotism, there are many other respected annual indices, such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, where Indonesia ranks 88the out of 168 countries and territories. And the World Bank’s analysis suggests a high, inverse correlation between a country’s ranking and measures of corruption.

As a strategy consultant with more than 40 years of experience working with governments throughout the region on complex, state enterprise and national transformation programs, I believe there are many useful lessons for President Joko and his team. That said, having worked on public and private sector strategy programs in Indonesia since 1972, I also recognize the uniquely complex internal and external challenges facing the president. Internally, Indonesia’s size, complexity and diversity, combined with weak institutions, a “work-in-progress” decentralization policy and a “combative” democracy, will stretch even the president’s skills as an orator and a conciliator. Further magnifying the challenge, President Joko took office at a time when the external environment is materially more difficult for Indonesia than for many of his predecessors. To succeed, the president will need good luck, good judgment – and good advisers.

My objective in this essay is not to pretend to have all the answers but, in the spirit of Spanish-American humanist and philosopher George Santayana, to seek relevant lessons for Indonesia from past efforts of other countries. Not just from the many published sources, but from hands-on experience.

The essence of my message is deceptively simple: sustainable economic growth requires policies and institutions that best align national aspirations and targets with external realities. The implication? Indonesia must be clear about its own aspirations (which is why Vision 2085 is important). It must have a capacity to analyze not just past but future drivers of growth; to increase chances of success, it must be able to not just adopt but adapt to lessons from other nations.

To illustrate, during the prolonged Great Depression of the1930s the Soviet Union was a high-growth economy, and prominent economists were arguing for central planning and “autarchic” policies of protectionism and self-sufficiency. However, nations that applied these lessons blindly in the trade and investment-driven global environment post-World War II missed out on Asia’s growth “miracle.” While India has been perhaps the most prominent example of this misalignment, it is important to recognize that for the first two decades after World War II the majority of the newly independent nations, including Indonesia, adopted variants of these prewar policies. To take this further, had it not been for the economic despair of four newly independent Asian nations – Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea, whose main postwar export was human hair – there might never have been an “Asian miracle.” During discussions with Goh Keng Swee, the architect of Singapore’s remarkable economic development, it was desperation that other policies were not working, rather than strategic insight, which led Singapore to open its borders to foreign investment and international trade. This model, adopted by the other newly industrializing economies (and eventually China), helped integrate them into rapidly changing global supply chains, and over time became the “new normal” growth model for virtually all emerging markets.

The argument I shall develop in this essay is that the new economic orthodoxy – trade and investment-driven integration into the United States and other large global markets – may, like autarchy in 1945, have become “conventional wisdom.” However, with the dramatic changes under way in national policies and attitudes in the United States and European Union, it may now be time for Indonesia to step back and challenge this conventional wisdom. This may be best done as part of an integrated national transformation process that will ask what will be the external drivers of future, not past, growth, and where and how Indonesia might become an early adopter of a new growth model.

I do not pretend this will be easy, but I will argue strongly that it cannot be worse than being a late adopter of a conventional wisdom that is past its “use-by” date. Given this perspective, my approach will be to draw not just on the policies adopted by the high-performance Asian economies, but also on the processes that they used to reach their – then relevant – decisions. It may be that pairing a best-practice national transformation process with new and creative thinking about the emerging external environment – geopolitical, economic and technological – will allow Indonesia to realize Joko’s Impian 2085 – and an immediate near-term jump in its ranking in the World Bank index.

In this essay, I will draw on lessons, not just of outcomes but of national transformation processes, where I had a hands-on role. This will include Singapore’s 1986 National Economic Planning process; “Vision Korea” in 1997; Thailand’s 1997 “Re-Engineering of Government”; Indonesia’s own October 1999 “BUMN Reform Program: Restructuring and Privatization to Maximize Value”; and Malaysia’s 2009 “New Economic Model” process – which led to a dramatic jump in its World Bank index ranking from 23rd to 6th in just one year. In addition to process, I will look at context, including the domestic politics and the external environment confronting the national leadership in each case. I will conclude with some initial ideas on how Indonesia might develop a transformation process that draws on the lessons of others, but applies them to Indonesia’s future – not past – external environment, as well its current institutional capacity and political realities.

Waves of “miracle” growth

The object of this section is to explore the reality – not the myth – of the so-called Asian Miracle in order to better understand the external environment of the region’s rapid Wave 1 and Wave 2 growth. The object is also to seed thinking on what it will take to win in the more challenging (new normal) international environment of slowing economic growth, declining trade growth and intensifying competition for foreign direct investment, which I refer to as “Wave 3.”

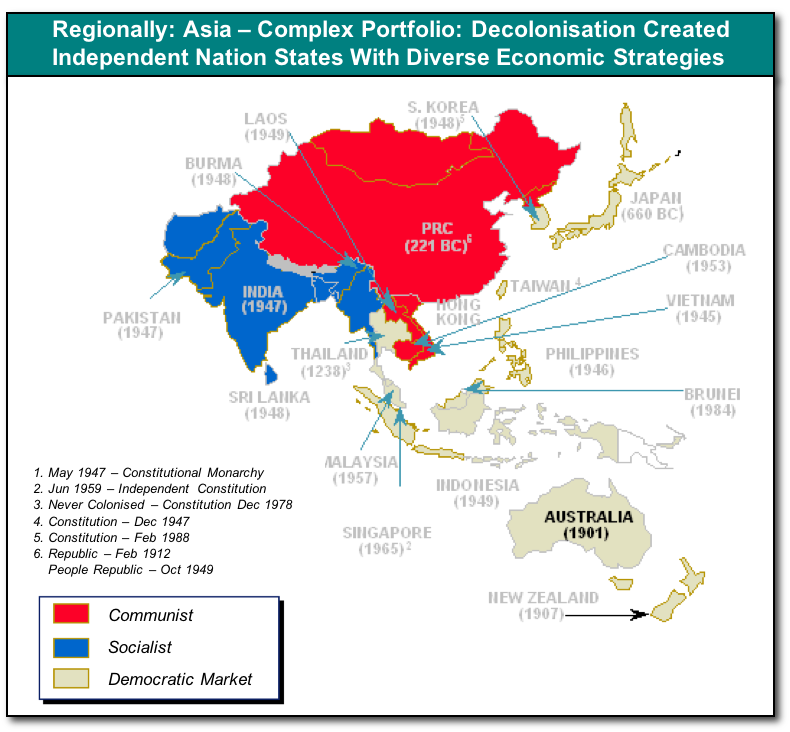

To better understand Asia’s post-World War II growth “miracle” must be to make explicit what we all know: that in practice there is no “Asia.” Our region is a complex portfolio of countries and economies at different stages of development, with diverse political and economic systems. Pre-crisis “miracle” performance was in reality linked to a unique and unlikely-to-be-repeated congruence of regional and global forces.

Despite the region’s heterogeneity, the one undeniable common link is geographic colocation. This accident of geography is combined with exogenous geopolitical and strategic decisions associated with both World War II, including Japanese occupations, and the independence and decolonization process that followed. The emerging bipolar Cold War and the resultant spin-off from massive US investment in military technology triggered the initial external “surf waves” of what eventually became known as “globalization.” This global realignment of supply chains provided a unique window of opportunity for countries in our region to take up economic “surfing” – ie, the accelerated development that results from the alignment of domestic policies with external growth drivers.

The “Asian Miracle” took place in two distinct “waves.” Understanding the distinction between the drivers of what I will call Wave 1 and Wave 2 is necessary to form a view on an emerging and distinct “Wave 3,” which I believe may require dramatically different policies for Indonesia to realize Impian 2085.

Wave 1 growth was US-driven and US-centric. The region’s early adopters of open economies – the four newly industrializing economies – depended primarily on trade and investment flows with the then dominant US economy. In Wave 2, China’s growth and global integration as a consequence of Deng Xiaoping’s “Four Modernizations” gradually led to a “G2” world, with China’s rapid growth complementing US demand. Both Waves 1 and 2 were characterized by rapidly increasing external trade and investment flows and accelerated integration into global and regional supply chains. Those economies that opened most rapidly to these flows captured the major benefits and most rapid gross domestic product growth during these two Waves – the largest restructuring of global manufacturing in history.

The combination of different starting points and different policy responses led to different results during the two early “waves” of growth. My argument is that the region’s initial “miracle” growth was an unintended consequence of one-off, geostrategic Cold War initiatives that collectively drove “globalization” of supply chains and which benefitted Asia over other regions. This latter factor was primarily due to a confluence of two factors: rapid postwar decolonization and the Cold War, which together triggered US concerns about where the “Bamboo Curtain” would fall in the region.

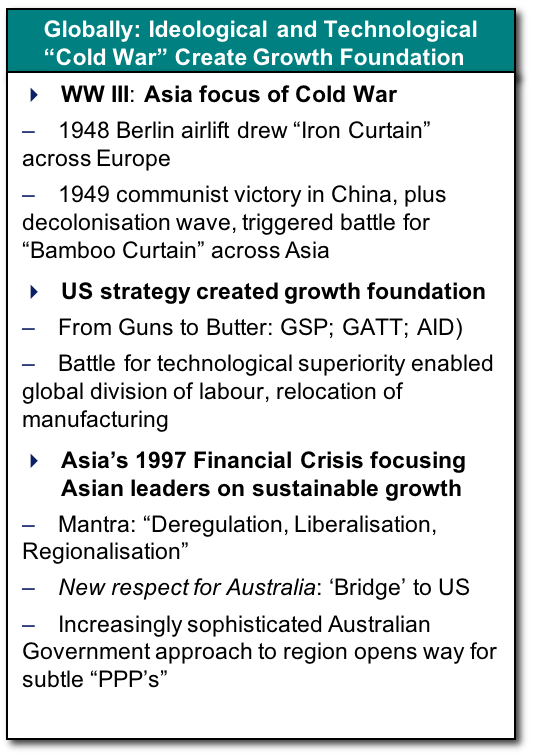

The three initial drivers of Wave 1 were all from US-led initiatives:

- The creation of new global – “Bretton Woods” – institutional architecture, designed primarily to isolate the Soviet bloc but as an unintended consequence enabled rapid growth in global trade and investment flows.

- The creation of new US domestic institutions as a response to what was seen as the threat of communism and, after the USSR Sputnik launch in 1957, as a response to the threat of war in space. This triggered huge US investments in dual-use technologies in, for example, transportation and communications. These in turn led to improved speeds and reduced costs of moving goods, people and information, and therefore contributed to the crucial ability to geographically separate production from consumption

- American-led strategies to provide favored, Generalized System of Preferences-based access to the giant US domestic market (then 50 percent of the world) for emerging market Cold War allies, especially Asian allies at risk from the expanding “Bamboo Curtain.”

The combination of the new institutions and new technologies effectively shrank the globe, not just the region, and became the engine of globalization. Wave 1 growth not only separated manufacturing from consumption, but as a consequence led to a fundamentally new global business paradigm in which giant multinational corporations (mainly American), such as General Electric, developed new ways of organizing their activities, which had important implications for regional policy makers. The emerging multinational corporations embraced a new, global division of tasks, functions and, as a consequence, also of labor.

The rapid emergence of multinationals was an important enabler of the Wave 1 globalization of supply chains and the ensuing global division of labor. The global division of labor led to accelerating global trade. This required parallel changes in international agreements to reduce tariffs and other barriers to trade. Achieving full benefit from these external changes also required domestic market liberalization and an openness to foreign direct investment. The consequence was unprecedented wealth creation for those countries that adopted the then-unfashionable, labor-intensive export-oriented growth model.

During Wave 1, just four newly liberated, resource-poor nations with little to lose (the “Asian Tigers” Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea), and whose hard and soft infrastructure had been devastated by World War II, adopted this model. In so doing, they demonstrated its effectiveness as a driver of growth. These economies had political leaders willing to “educate” their people to change attitudes toward investment, often in cultures with traditional beliefs that foreign investment destroyed jobs and was a form of economic colonialism.

If globalization was indeed the driver of Wave 1 of Asia’s miracle growth, then this was running out of steam after the second 1979 oil price shock and might have died on Nov. 9, 1989, with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the symbolic end of the Cold War. However, help for a new wave of market-based restructuring of global and regional supply chains was at hand from an unlikely source: China, the world’s most populous, and still communist, nation. In China’s “Four Modernizations,” it began a trade and investment-led integration with the global economy while maintaining its monopoly on political power.

By the 1980s the combination of China’s labor cost advantage, the opening of its markets and the unanticipated boost from the G5 meeting convened in New York in 1985 (the Plaza Accord) to address America’s “triple deficit” became the catalyst for reforms that drove Wave 2. These reforms included growth-oriented and currency realignment policies that led to a dramatic appreciation of the yen/dollar rate, and therefore to an acceleration of investment from Northeast into Southeast Asia. Together, these events triggered the second regional growth tsunami that I refer to as Wave 2 (regionalization-driven) growth.

In the next few years a number of Southeast Asian economies, including Indonesia, became the second generation of high-performing Asian economies (HPAEs). Resource-rich and hitherto import substituting nations including not just Indonesia but also Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines began to emulate the original HPAEs and benefitted from a rapid jump in investment from Japan/North Asia as well as the United States. In Thailand alone, inbound investment in the 18 months after the 1985 Plaza Accord was greater than in the cumulative preceding 18 years. However, Indonesia and the other commodity-rich Southeast Asian nations like Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand simply “grafted” export-oriented clusters onto their inherently import substituting culture and institutions. Their institutions and political systems remained little changed and growth still remained heavily dependent on commodities.

At the time the little-understood Asian “miracle” led to government overconfidence and unsustainable flows of short-term money into the region’s still small capital markets, and thus to unsustainable “Asian bubble” valuations. When confidence faltered, as it began to do in mid-1997, it ultimately triggered a pan-regional run on Asian banks and currencies. The crisis highlighted the fragility of Indonesia’s economic policies and institutions and there was a dramatic collapse of the rupiah from 2,500 to 17,000 against the dollar. This contributed to mass insolvency of the heavily dollar-indebted and often publicly listed Indonesian conglomerates, mass layoffs and to unprecedented social unrest and student protests. The violent overreaction to these protests by elements of the country’s security forces triggered political change, ending the 31-year regime of Soeharto.

The asymmetric adoption of policies to enable integration during these first two waves is well illustrated by the diversity even between the 10 geographically collocated members of Asean. Singapore, an early newly industrialized economy, now has a per capita GDP that is 55 times greater than (very) late adopter Myanmar.

The Wave 3 “context” will in my view grow even more challenging. During the Cold War, a strong and confident United States was committed to opening its domestic market to strategic emerging market allies. However, with the recent anger and resentment against imports and immigrants that presidential candidate Donald Trump has tapped into, it is likely that the United States will become a less accessible market and potentially a less dependable guarantor of freedom of the regional seas, skies and market access, and of the region’s still fragile emerging democracies. My argument is that what worked so well for even late adopters such as Indonesia during the global geopolitical and economic context of Wave 1 and Wave 2 growth may no longer be appropriate during the far more challenging global environment of Wave 3.

Aligning domestic policies with external realities

The objective of this section is to draw lessons for Indonesia. These lessons include not just policy and institutional responses to the Asian crisis, but also how they designed their national transformation processes in ways consistent with their national political and institutional capabilities. This approach is not designed to offer any easy solutions to Indonesia’s complex challenges, but to suggest lessons for Indonesia’s leadership today as it pursues President Joko’s Impian 2085 in the more challenging Wave 3 environment.

To assist Indonesia in selecting its own unique process, I begin with a “map” of five distinct models selected from those with which I have been personally involved. Four are from Asean, including one from Indonesia on state-owned enterprise reform, and the fifth is from South Korea.

The framework structure reflects the need to design a process that considers the “strength” of the government and the “national sentiment,” or the degree to which the voting public perceives there is a strategic or economic threat that requires urgent national action, and thus confers full authority to its leadership to take rapid and sometimes painful action.

Let me now illustrate the framework by briefly applying it to five case models.

Case 1: Singapore

In 1985, Lee Kuan Yew and the People’s Action Party were politically dominant and would rank as high (authoritarian) on the Y axis. However, after rapid growth and near full employment, Singaporeans’ confidence suffered a major blow in the shock 1985 recession. While objectively, Singapore might have been judged to be still in a very healthy economic state, years of annual warnings by Prime Minister Lee in his televised National Day address that Singapore faced an existential threat to its existence allowed this leader, then unchallenged, to take decisive and nationally supported action.

While we shall not go into detail, the immediate actions included the creation of a high-level public-private National Economic Committee.

In less than a year, the committee and its various subcommittees had developed both analysis and a range of far-reaching policy prescriptions that were rapidly approved by Parliament and rapidly rolled out. This resulted in a rapid and sustained return to growth. Lee Kuan Yew later referred to this report as a “turning point” in Singapore’s development.

Case 2: Thailand in 1986 and 1997

Another fellow member of Asean, Thailand in 1995-96 was experiencing slowing economic growth and a succession of weak and short-lived governments. In this environment, the government at that time chose not a far-reaching top-down national transformation, but a technocrat-driven attempt to honor Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda’s 1986 commitment to “cut the red tape, but this time not lengthwise.”

Because Thailand ranked low on both government authority and economic anxiety, we characterized it at the time as “fatalistic.” It took another 11 years before a foreign consulting firm, US-based Booz Allen Hamilton, supported by the then independent and prestigious Office of the Civil Service Commission (OCSC), was helping the prime minister’s office. The approach used to attack Thailand’s red tape came from the private sector and the project became the “Re-engineering of Government.” Unlike Singapore’s top-down command model, this program was driven below the level of the divided cabinet and, along with the OCSC, key ministries were selected in a negotiated “coalition of the willing” to streamline, improve service levels and enhance transparency.

Case 3: South Korea

In 1996, South Korea was facing economic challenges a full year before the Asian financial crisis hit. The complexity of public and private sector stakeholders, a population without a shared sense of crisis and a less authoritarian political system required a different approach. The outcome of the initial diagnostic by Booz Allen Hamilton (I served on the advisory team) was a truly national, stakeholder-driven and media-supported process called “Vision Korea.” With strong stakeholder support, this process moved fast to prioritize recommendations and translate them into action. The effectiveness of this process contributed to the relative success of the South Korean government in navigating the 1997 crisis.

Case 4: Indonesia 1999 BUMN reform

At that time, Indonesia’s approximately 159 state-owned enterprises (BUMNs), while nominally owned by the Ministry of Finance, were pre-1998 typically controlled by the assigned sectoral ministry. Most had also become inefficient sources of campaign funds and patronage appointments that argued for continued protection. Collectively these policies deterred foreign direct investment and the employment of foreign specialists, because FDI was then seen – as we now know incorrectly – not as job creating but as competition for a fixed stock of jobs.

Case 5: Malaysia’s new economic model

While Indonesians suffered a lengthy economic tsunami, in Malaysia the governing Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition preserved its political legitimacy. Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad was thus able to use his autocratic powers to implement a highly controversial policy of pegging the Malaysian ringgit. In addition, in January 1998 he also created a cross-party/public-private National Economic Action Council that he chaired, combined with accelerated banking reforms. Taken together, these decisive decisions preserved currency and political stability, and combined with a high level of government stimulus spending, led to relatively rapid recovery. Malaysia may, however, struggle with the shift from Wave 2 to Wave 3 as public sector investment crowds out the private sector and with the political legitimacy of the dominant United Malays National Organization (UMNO) party now threatened by the scandals surrounding current Prime Minister Najib Razak and rampant vote-buying in the recent Sarawak state election.

In 2009, UMNO was facing a more challenging political opposition and an economy where private sector investment had remained stagnant since the 1997 crisis. With its widespread system of economic subsidies, the population did not yet share Najib’s sense of looming crisis, so the government could not take the strong top-down Singapore route, and with a less vibrant private sector did not feel the “Vision Korea” model would be as effective in Malaysia. This, combined with the complexity of the ruling BN coalition, made the governance of the transformation very complex. Najib ultimately chose to create of a new National Economic Advisory Council comprised of nine highly respected and politically independent technocrats.

Implications for Indonesia

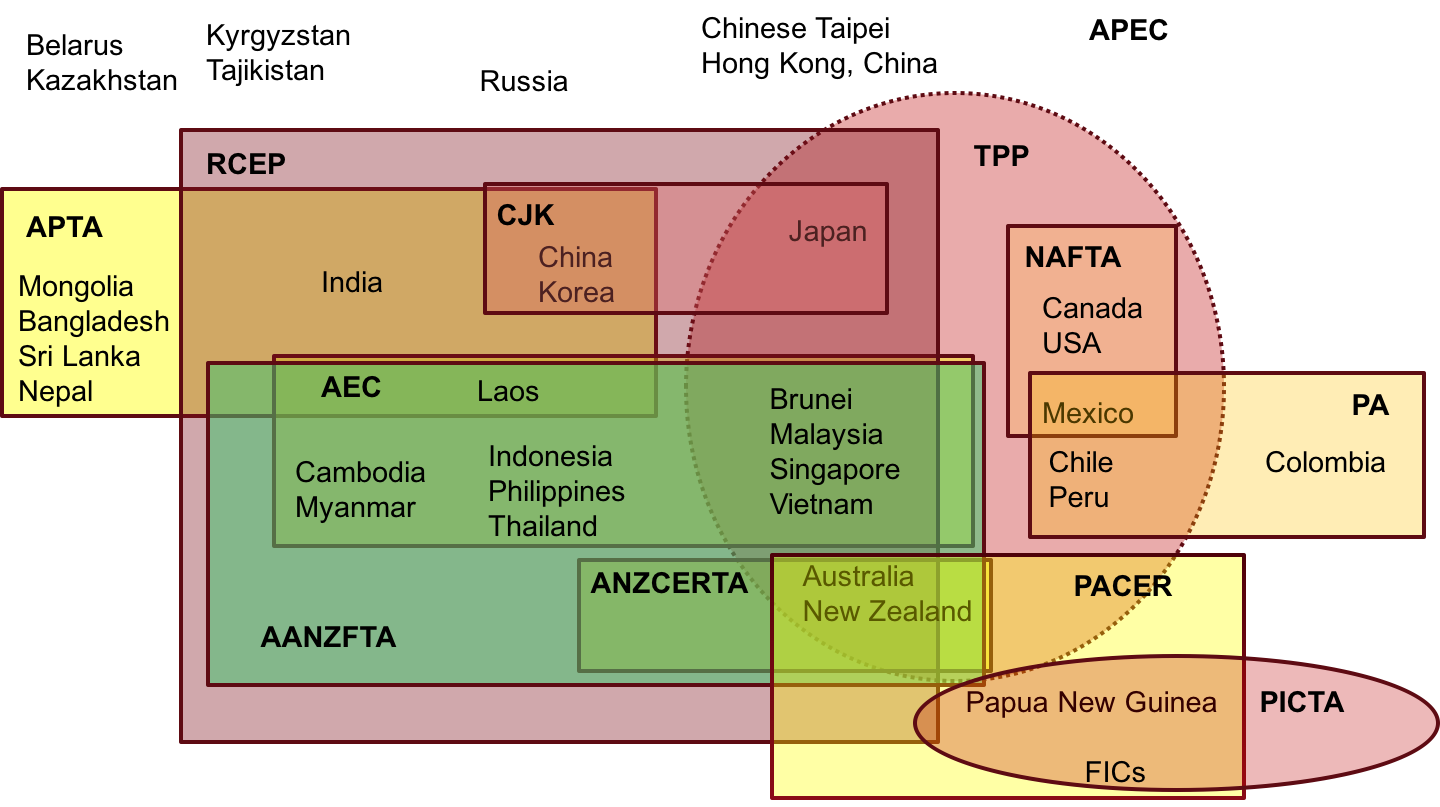

As we look for lessons for Indonesia, let me once again reinforce the importance of aligning domestic policy responses, not with history, but with the current and future external environment. This external environment differs greatly from the trade-driven era of Waves 1 and 2. The World Trade Organization’s efforts to achieve global alignment on tariff reductions has been replaced by a “noodle bowl” of institutions plus complex and overlapping trade agreements (as shown below).

During Wave 1 and Wave 2, regional integration contributed to and was driven by growth in intraregional trade, which was increasing at around a 30-percent compound annual growth rate – more than three times faster than growth in gross domestic product. In Wave 3, this ratio of growth in intraregional trade, GDP has been declining rapidly and approaching 1:1 parity. As the engine of international trade weakens, Indonesia’s challenge will be to accelerate the dismantling of barriers to internal trade-driven integration as a driver of Joko’s goal of more inclusive national development.

Based on these and similar experiences around the world, we would caution again that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach. But, we have created a 10-step “wheel” as a guide to best practices in managing a national transformation program once lessons from the various models have been considered and adapted to Indonesia’s circumstances.

To summarize the key lessons: national transformation programs require top-down leadership, and a realistic self-assessment of the underlying current challenges and the areas where there are major gaps between this and an aspirational vision of the future. The leaders of the overall transformation and of individual initiatives must be supported by a strong and independent secretariat that, often working with outside experts, creates and publishes a road map of strategic programs, program sponsors and tangible measures of success. This process should be as transparent as possible and will include regular feedback to the government and public.

The external environment will be more challenging for Indonesia if it seeks to follow solely the trade and foreign investment-driven growth waves: the globalization-driven Wave 1 or regionalization-driven Wave 2. In the final section of this essay, I will argue that if Indonesia takes a more holistic and strategic approach to strengthen its institutions, accelerates the rollout of infrastructure to “shrink and integrate” this huge archipelago and leverage its unique assets (size and strategic location), then the country can chart a unique course to help stabilize not just the region, but the world.

As a young, post-Cold War president, Joko can navigate away from a bipolar dependence on any of the large powers (including nuclear-armed ones) and invest in extending Indonesia’s influence as a founding member of the Nonaligned Movement; in key multilateral and pan-regional strategic and economic organizations such as the G20 and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum; and recommit to APEC’s 1994 Bogor Goals and the vision of the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific.

Indonesia must, however, also leverage its other strategic assets, both domestic and international. In addition to the multilateral economic forums mentioned above, Indonesia is also in a position to contribute as the world’s third-largest democracy and, in a world now divided not just by economic power but also by religion, as the world’s most-populous Muslim-majority nation. With a broad-based approach, Indonesia has the potential to chart a unique course in Wave 3.

Given the lessons from the cases, what might be an optimum approach for Indonesia? While the World Bank and others credit it as being one of the high-performing Asian economies, in practice Indonesia missed Wave 1 and was a late arrival to Wave 2 growth. As a late arrival into Wave 2 it accrued some gains, but these were not supported by the far- reaching domestic institutional and bureaucratic reforms undertaken by the four Asian newly industrializing economies. In addition, while a good start, the 1999-2000 state-owned enterprise reforms were positive but incomplete; national attitudes toward foreign direct investment remained ambiguous at best; and there has been insufficient investment in human capital.

In this section, I will provide only a few seeds for a national discussion about what the external environment might look like in Wave 3 and where and how Indonesia has an advantage versus other competing nations to “ride the biggest new waves.”

While international and domestic trade and foreign direct investment will remain important components of Indonesia’s Wave 3 strategy, the debate must quickly be widened to include domestic policy and institutional reforms that are focused also on better integrating the domestic market and improving total factor productivity. The good news is that the size and diversity of Indonesia’s domestic market offers huge opportunities to achieve gains from domestic trade. Indonesia’s challenge will be that protection has left it with weak economic institutions that remain fragile and are often politically influenced and inward-looking. Large parts of the economy remain dominated by state enterprises. There is need for the type of holistic economic strategy process that Singapore undertook in 1984-85, along with subsequent heavy investment in institutional capacity, policy reform and skill-building.

President Joko has the advantage of having been elected on a platform of change, not just for the elites but for the whole nation. The challenge today will be to fast-track enough high-impact and high-profile reforms to sustain his political capital. With this, he can continue to educate voters on the need to open the economy to greater international and domestic competition and reforms. There will be short-term pain preceding the longer-term gain, so the president must consistently reinforce the plan and report on progress to his cabinet, the House of Representatives and directly to the Indonesian people.

In concluding this essay, I wish to make the case for a bold national plan, and believe Indonesia can lead the way through the following:

- President Joko has the necessary political legitimacy, a clear long-term vision with short-term targets, and the advantage of lessons learned from other regional transformation programs.

- New technologies can now enable the development and rollout of e-government to “obliterate” red tape, overcome national-regional policy and process overlaps, enhance the quality and value of public services to Indonesia’s tech-savvy people, and reduce the space for corruption, collusion and nepotism.

- These new programs can be funded by reconstituting the successful state-owned enterprise transformation program rolled out in 1999-2000 to enhance the value of Indonesia’s state companies – the gap was $100 billion at that time. More than half of that enhanced value was believed to be able to come from just one sector: energy and mining.

The focus for Indonesia must be on integrating its large but fragmented local markets, and on increasing the returns to all factors of production in all sectors of the economy. This will require a complex combination of policy reform (like in Singapore and South Korea); streamlining red tape (Thailand); enhancing state-owned enterprise competitiveness (Indonesia 1999); plus enhanced national infrastructure investment. Underpinning all of this must be political will and institutional capacity building.

However, time is of the essence. With the short political cycle, President Joko will need to soon announce a small number of high-impact, transformational national development initiatives. These should be high profile, inclusive and combine near-term tangible impact with the creation of a “virtuous cycle” of reform. This is not easy. In the balance of this section, my objective is to suggest a selected portfolio of actions that will provide both tangible short-term gains to build support, while in parallel investing now in the longer human and physical capital required to realize Impian 2085.

Let me, therefore, conclude by proposing three large initiatives for debate, discussion and possible inclusion in a “Vision Indonesia” initiative:

- Design and announce a national transformation project as a cross-party supported, technocrat-led initiative from President Joko but with day-to-day leadership assigned to a respected technocrat minister with business experience, and supported by nationally respected figures. To support this initiative, the president could draw on a mix of existing agencies and independent academics and institutions dedicated to government reform.

- Launch a combined national e-government/re-engineering of government initiative. With its size, complex national and regional electoral process, and incomplete implementation of decentralization, Indonesia is bound in red tape even more complex than encountered by Thailand’s Prime Minister Prem in 1986. The mantra of business process re-engineering (“Obliterate, don’t automate”) remains valid, since 1986 technology has advanced dramatically. Rather than tackling bureaucracy and red tape at central and regional agencies in isolation, President Joko has the power, and hopefully the determination, to tackle them holistically. Throughout, the president would take personal overall responsibility as a critical, high-profile national initiative that will eventually touch the lives of every Indonesian and underpin the national governance model required to reach Impian 2085. The lessons from other e-government programs, such as in Sweden, are that they can achieve substantially more effective coordination of the central and regional governments.

- Relaunch the 1999-2000 BUMN Transformation and Value Creation Program, to fund a national transformation program. The proven program in 1999-2000 to transform state-owned enterprises began by quantifying the gap between their current and potential value. The value gap at that time was approximately $100 billion. Today, it is now $270 billion. The governance model established in 1999 by Indonesia’s Ministry for State-Owned Enterprises worked very effectively during the initial program and could be quickly recreated under an overarching national transformation model led by President Joko.

Conclusion

The case I have sought to make in this essay is that our region’s post-World War II economic “miracle” has occurred in two distinct waves: globalization and then regionalization. We are now moving quickly into a third wave, which will require very different strategies and policies to win. -During the first two waves, the winners integrated into rapidly changing global supply chains and rode on to enjoy dramatic growth through international trade. The winners linked external growth with domestic development by improving skills, plus physical and institutional capacity.

However, with the continued decline of the World Trade Organization and the increasingly complex and politicized “noodle bowl” of bilateral and multilateral agreements, future growth will depend less on exogenous factors and more on skill-building and national institutional capability. This will reduce infrastructure and policy barriers to domestic market integration, thereby enhancing total factor productivity. While Indonesia was a latecomer to trade-driven growth thanks to Waves 1 and 2, the nation has the potential to be a leader in the emerging Wave 3 environment.

Ian Buchanan is the former regional head of SRI International and Booz Allen Hamilton, and has more than 40 years of experience in Indonesia and the region. He is currently Senior Executive Adviser to PwC Strategy& Indonesia.

Ancient scourge exposes Indonesia's health care flaws

Ancient scourge exposes Indonesia's health care flaws  Border Five-O : Protecting Indonesia's territory

Border Five-O : Protecting Indonesia's territory  Indonesia's next terrorist fight

Indonesia's next terrorist fight